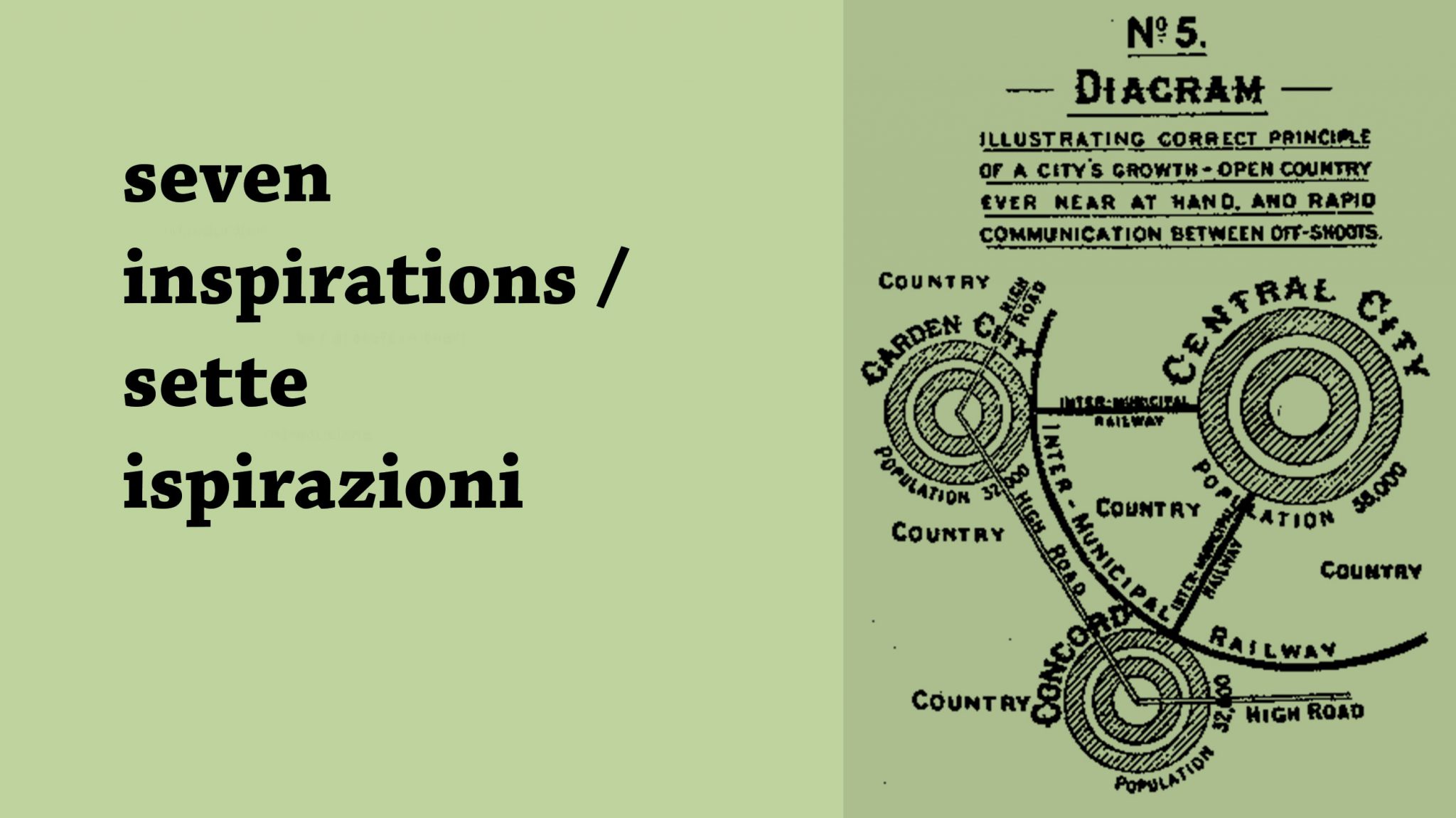

In 1898 Ebenezer Howard published A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, a milestone text for a new pact between city and nature that was republished in 1902 in a new version with the title Garden Cities of To-Morrow.

Howard’s proposal for addressing social inequalities, problems of pollution and traffic and risks of hygiene and public disorder resulting from the overwhelming urban growth linked to the processes of industrialization, was to design urban communities of 32,000 inhabitants around London and the larger cities. Cities with low density, with services and facilities for the community at the heart and around them a system of circles of homes surrounded by nature, able to combine the advantages of urban life and those of the countryside.

The first “Garden Cities” as examples and public property were built in 1903 in Letchworth and in 1920 in Welwyn and were the inspiring model for an important trend in planning and architectural thinking that ran through the 20th century, with names ranging from Lewis Mumford to Clarence Stein, Henry Wright to Clarence Perry and from Rexford Tugwell to Arthur Morgan.

A century later, the proposal for the creation of a worldwide system of “Urban forests” consisting of buildings that are homes to nature within their own structures is facing a different scenario, that of parts of the world where the urbanization of large numbers of peasants will for many years yet be an unstoppable process.

This scenario sees agriculture – agriculture that is versatile and full of variety, finally able to produce food for the different urban social groups – again becoming a key resource for large metropolitan areas.

This is a scenario which requires a strict reduction in the consumption of natural and agricultural soil produced by the continuous horizontal extension of urban areas with low building density, and that makes it increasingly difficult for local governments to deal with the social, economic and environmental costs of large city management.

In this scenario, the design of small high density “vertical cities” featuring an intensity of life that reduces the cost of managing energy and transport services by proposing a new balance between the urban, agricultural and natural spheres can become a significant opportunity.

But to combine the density given by a vertical growth of buildings and the biodiversity resulting from a new balance between nature and city, urban planning is not enough. The visions that generated large scale transformation processes of territories and areas were able to combine large scale city planning and perspective with the creation of individual and timely architectural devices, repeated throughout the territory. So in the same way that the single family house with garden a century ago was the elementary module as expressed in Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities scenario, the tree-tower or “vertical forest” could become in the coming years the device – repeated with endless variations – that will allow not only to engage ecosystems of biodiversity in the built city environment, but also to create a new form of city: the Urban Forest, a City/Forest where architecture neither binds nor restricts nature, but instead accepts it as an original component part.