Images

Project

Stefano Boeri, Giovanni La Varra, Gruppo A 12

Location

Milan, Italy

Year

1994

Client

Associazione Frontisti Ferrovie Nord Milano

Project team:

Stefano Boeri

Giovanni La Varra

Gruppo A 12 (Gianandrea Barreca, Antonella Bruzzese, Eva Robert, Peter Scupelli, Valeria Chiarla, Massimiliano Marchica)

with Nicoletta Artuso, Andrea Balestrero, Marco Bonelli, Cristina Cassanello, Maddalena De Ferrari, Fabrizio Gallanti, Matteo Leonetti, Fabrizio Paone, Silvia Pericu, Elena Rosa.

Graphic design: Mario Piazza, Simonetta Rocco (Achilli & Piazza e Associati)

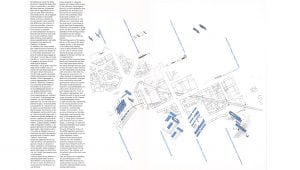

Winner project of the competition promoted by the Associazione Frontisti Ferrovie Nord Milano the Railway Alphabet proposes to give the railway a new visible, urban shape, even in places where a cutting is covered, in the attempt of bringing to life a new interactive principle linking the railway to the city, a generai principle that was not an imposition, but which remained resolutely sensitive to the linguistic variations of the city.

The urban lexicon: grammar of FFNN

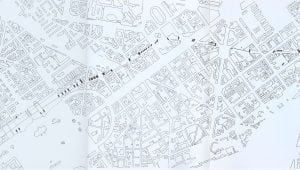

The tracks need to be covered to reduce train noise levels, but this can also be a way of recovering e sequence of in-between spaces for everyday urban behaviors and habits. Private, inner spaces often curtained off behind a row of back views; spaces that are in danger of becoming empty, deserted and unused, however quiet they may be in the end, once the tracks are covered.

The project, on the other hand, proposes to give the railway a new visible, urban shape, even in places where a cutting is covered. As in wax-casts, when one matter is replaced by another while retaining the same shape, so the railway fine remains visible in among the city blocks, even though it is physically imperceptible.

But this visibility must be in keeping with the peculiarities of Milan’s Northern Railway and its relationship with the city. This particular characteristic is reflected today in the trackskeeper system used constantly, not only in the regular, horizontal sections, but a/so when the gradient of the railway and its altimetrical position in relation to the city varies.

This is how we interpreted the requirements /aid down for the competition, and we tried to bring to /ife a new interactive principle linking the railway to the city, a generai principle that was not an imposition, but which remained resolutely sensitive to the linguistic variations of the city.

Like a proverb or a popular saying, the railway today is part of the idiomatic language of the city, in which dramatic disagreements are avoided, and boundaries of meaning and accent left undefined, clear, fluent and uniform, it is nevertheless sensitive to the differences it encounters; and like a proverb it continues to make itself heard repeatedly. Therefore, our proposal is to lay down the basic for a new urban alphabet of the railway, taking examples from the stretch between Cadorna and Bovisa station.

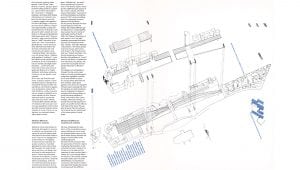

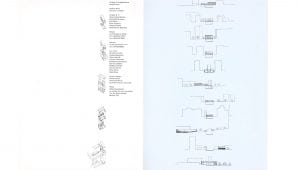

The starting point of this alphabet, as in the case of the trackskeeper system, is the drawing of an elementary module,

a sort of basic element which can be used in several fundamental drawings and can be adapted to the part of the city it is destined for.

lntroduced into spaces between blocks and backyards, but also into wide open spaces where the tracks emerge into the light of day, this basic urban element can be modulated, and by lying with one side or the other on the ground, by joining it to other modules or repeating the same one, the pattern changes, thus constituting articulate grammatical terms and clauses. This basic, multi-functional module is a parallelepiped complete with a fixed structural grid measuring 3,5 x 7 x 21 m .. The shape is elementary, but flexible enough to bring a wide range of spaces to life. lndeed, the parallelepiped varies in type and function depending on its resting position on the ground, on the combination it is used in, and the type of space it encounters. It can serve as infrastructure (bridge, footbridge, roof covering, support for soundproof panelling … ), living space (residential and reception areas or workshops .. .), parkings, or mark the boundary between open spaces and urban borders.

Thus, by fitting the /etters of the FFNN together, grammatically and syntactically, a sort of urban alphabet is born. Without ever deserting the railway line, this modu/e is used to compose numerous shapes that interpret both the urban spaces that have been re-discoverede thanks to the covering of the railway, and the places where the track runs in the open.

Like the letters of an alphabet, the parallelepipeds of the Milan’s Northern Railway gradually become words, and conversation between Milan and its railway starts anew.